René Harrop – Autumn Essentials for the Henry’s Fork

Det är många skandinavier som drömmer om en höstresa västerut – till öringarna och regnbågarna i Klippiga Bergen. De högt ställda förväntningarna kan sluta i ett fiasko. Flugfisket i Henry’s Fork, Idaho, USA, är en rejäl utmaning på många vis. Visst finns det mängder med fisk men för att lyckas krävs det bland annat försiktig vadning, långa och tunna tafsar och små flugor. Den amerikanska flugfiskelegenden René Harrop, som bor vid de berömda strömmarna, ger dig hjälp i dina förberedelser.

René Harrops text översattes och publicerades i FiN nr 4 2017. Här får du läsa den på originalspråket.

By René Harrop photo Bonnie Harrop

At high elevation where I live along the Henry’s Fork in Idaho, autumn generally arrives considerably before its designated date on the calendar.

In most years, the first frost arrives in late August. By early September, much of the vegetation has begun to assume fall colors that will illuminate the pine forest with a patchwork of red, orange, and yellow until winter arrives or the dying leaves are swept away by strong winds late in the season.

Snow on the surrounding peaks becomes a common sight in the landscape from about mid-month forward and though seldom lasting more than a day or two at a time, fishing in a snowstorm or its aftermath is not an unusual feature of September in the Rocky Mountains. Here, rain is a greater likelihood until late October when an approaching winter becomes more than an idle thought.

Early autumn temperatures can be summer like but a fleece jacket is standard for most mornings and those times when a stubborn thermometer dictates extra protection throughout the day.

Remembering that seasonal changes occur rapidly at high elevation, any visitor should be prepared for winter conditions with proper protection that can prevent the loss of a day’s fishing.

In autumn, nearly any river in the vicinity of Yellowstone becomes a smaller version of itself in terms of the volume of water it carries. This can be an advantage to the angler in some respects such as ease in wading and the ability to see trout. But there is another side to this coin.

A thinner flow can prompt seasonal evacuation on some portions of a stream simply because of inadequate depth to provide the survival needs of trout. This behavior is of particular importance for someone who might have experience on the Henry’s Fork during summer months when water levels are higher and the trout are well distributed. Expectations based on familiarity can be dashed when the individual arrives on this river for the first time in autumn to find formerly productive stretches to be nearly vacant of trout.

The highly popular Harriman Ranch is known to be a place where the wading angler can find comfort through much of its nearly eight mile length. Some of this comfort is found in the broad flats where water may be little more than knee deep. In autumn, dense aquatic vegetation reduces the open water in these areas by as much as fifty percent when the river flows at perhaps only half of what is found during summer. Therefore, it is understandable that trout would migrate to areas of greater depth and faster current when those conditions are present. This can mean that fewer miles of the river offer the same opportunity in fall as in summer but, fortunately, there are also fewer anglers to compete with for the most productive water.

While far from deserted, the number of anglers frequenting the Henry’s Fork shrinks rather dramatically as the weather begins to cool, although September is still considered to be a fairly busy month. For this reason, some visitors will accept a higher risk of weather disruption by planning their trip for mid to late October. By this time, only the hardiest of souls will be observed on the water when a thin layer of ice may line the banks and the evening air carries a distinct bite. When shrinking hours of daylight are factored as well, it is not unusual to roam freely along even the most assessable points on the river.

My fishing objective is the same as anyone who fishes the Henry’s Fork, though I admit that living here has distinct advantage. Rather than sitting in one place and hoping for the opportunity of fishing to a big trout, I usually find myself walking and watching. A trout rising in open, shallow water can sometimes be detected from a distance of nearly one hundred yards, but approaching a fish is not usually as easy as finding it. Far too many opportunities are lost to careless wading. Moving too quickly is always a bad idea in water that may be less than knee deep. Clumsy movement sends trout warning sound waves that travel in all directions through water, which makes the careful placement of each step a vital matter regardless of the direction of approach.

Any motion overhead will send a trout that is accustomed to danger from above into a defensive mode. The shadow of a fly line can be as threatening as an aerial predator like an Eagle or Osprey. The sight of an angler or just the movement of a fly rod can also end a promising encounter in an instant.

Like most fly fishers, I recognize the advantage of a fly first presentation made from a quartering angler upstream of a feeding fish. This can be accomplished rather comfortably in waist deep water but the method assumes a greater risk in reduced depth and extreme water clarity. The difficulty lies in staying out of the trout’s view, which generally means that a much longer cast is required. Working from the side with a reach or curve cast lowers the likelihood of being spotted while still getting the fly downstream ahead of the leader.

For somewhat difficult reasons to understand, many fishermen I observe on the Henry’s Fork are reluctant to utilize the most efficient method of approaching a trout in low, clear water.

Through the history of fly fishing, an upstream cast to a rising fish has been the fundamental way of presenting a dry fly. There is no simpler way of avoiding detection than to make a basic straight line cast from behind, and there is no better way of getting close to a wary fish.

I consider an upstream presentation to be a viable option in any season but it becomes the cast most frequently relied upon in the extreme conditions of fall.

Often, the largest trout are the most secretive in their choice of a feeding position. A big fish tucked tightly against the bank or an exposed weed bed can create surprisingly little disturbance as they pluck drifting insects from the surface. The precise accuracy required to place the fly into a position of acceptability can be as demanding as any situation that might be encountered.

Surprise at what lies beneath a mere dimple in the surface is not an unusual reaction when the fly seems to just disappear and the rod is lifted to find weight that is far beyond what is expected.

A large, savvy trout will take position in front of a large rock where its feeding activity will be disguised by the current breaking over or around the in-stream structure.

Looking beyond the obvious holds the benefit of discovering a prize that will likely be overlooked by the impatient or unobservant angler.

Much of the challenge of fishing the Henry’s Fork in autumn is centered round the difficult currents created by water flowing over heavy aquatic vegetation.

Any discussion of presentation must include not only accuracy but the ability to provide enough leader slack to allow the fly to follow conflicting currents that promote uncommonly severe drag.

Other than an upstream delivery, any casting angle is a candidate for deftly administered mending technique. Feeding line behind the cast is an effective means of extending the drift of a fly that is delivered well upstream, thereby reducing the length of the cast needed to reach a feeding trout.

Always the enemy in any season, problems associated with a dry fly that does not move in unison with the current can become a nightmare in autumn.

Intensified by several months of near constant angling pressure, the tendency of a trout to reject a floating artificial on the basis of drag is perhaps the most difficult obstacle to overcome in the late season. A perfect cast becomes worthless if adequate slack is not included to allow the fly to move freely as it drifts toward the fish. Mending the line to add slack in the leader subsequent to the arrival of the fly on the water can be a useful tool in some situations but slack line accuracy in the cast should be the first priority.

Most anglers understand the advantage of a long leader when attempting to deal with trout in a condition of heightened awareness, and twelve feet is about minimum in the fall. Not as well-known is the benefit of a longer tippet that will help to soften the arrival of the fly while lowering the potential for drag. For me, thirty six inches of tippet is about standard but in extreme conditions of difficulty I will increase that length by a foot or more.

I am convinced that an inaccurate imitation presented without drag is more likely to be accepted than a close match that does not move naturally with the current. However, any angler that fishes the Henry’s Fork should expect to be greeted by extremely selective feeding behavior of trout sophisticated by catch and release management.

With dry fly fishing as the primary objective, hatches are perhaps the most important feature of the Henry’s Fork. Known for its great diversity of trout attracting insects, the river provides some relief from the complexity of matching the hatch in the prime months of spring and summer.

Terrestrials like ants, beetles, and hoppers may be present into early October as will some caddis and mayflies such as Tricos, Callibaetis, and Pale Morning Duns. Having a few of these flies in your vest is good insurance but they become mostly incidental as temperatures grow colder, which is usually about mid-September.

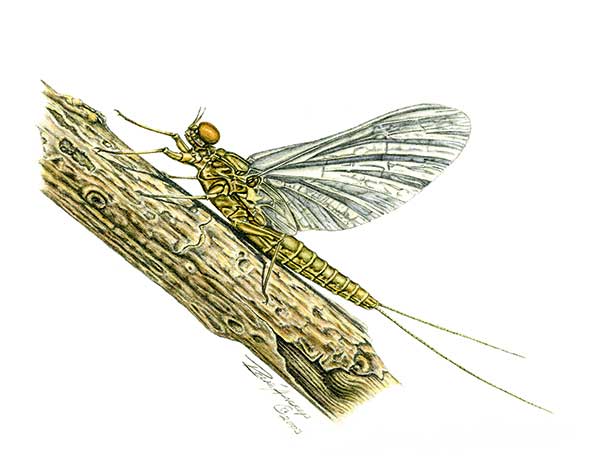

Characteristically small in physical size, Baetis are the predominant mayflies of autumn. Ranging from size eighteen on the large end to size twenty four on the lower extreme, Baetis or Blue Wing Olives seem to thrive in conditions far too harsh for other mayflies.

A Baetis hatch is almost an assured feature of an autumn day, and their emergence can extend well into November. The most promising opportunity, however, often occurs during overcast skies with light rain or snow and the temperature hovering just above the freezing mark. Hatches of amazing density can occur in these conditions and there are times when there are actually too many flies on the water.

Though notably less tolerant to cold weather than Baetis, Mahogany Duns are considered somewhat a bonus hatch from the beginning to about the mid-way point in the season. At a solid size sixteen, Mahogany duns will dwarf the more prolific Baetis that average no larger than size twenty.

With superior size as its most attractive feature with respect to trout, Mahogany Duns are not generally seen in tremendous numbers during an emergence period. Even in relatively sparse presence, however, the reddish brown insects are a fall temptation that trout seem to find difficulty in resisting. For this reason, a Mahogany Dun imitation is often the first fly I will try on a surface feeder, even when no naturals appear on the water. Though not one hundred percent reliable, this tactic based upon a familiarity factor can work surprisingly often even during a strong Baetis hatch.

More often, however, I expect to be faced with a stubborn fish that will not deviate from being locked into a specific size and stage of the most available insect at any given time. With this in mind, I carry an assortment of patterns that address each stage of the life cycle, which includes nymphs, duns, and spinners. Interim patterns known as emergers are also an asset as they attempt to imitate the most vulnerable phase of emergence.

While a size sixteen will cover any Mahogany Dun pattern, Baetis are a different matter. It is not uncommon to find three different sizes of the generally olive colored mayflies appearing on the water together. It can be a mistake to assume that trout will respond more favorably to the largest insect available, although it can certainly serve as a starting point. Given a choice, I will always try to tempt a fish with the largest fly possible, but I find that the smaller sizes of Baetis are usually most dominant in terms of numbers associated with a hatch. This observation helps to explain why a size twenty four is frequently more effective than a size twenty, and why, overall, a size twenty two seems to be the most reliable size.

Not to be forgotten or ignored in the shadow of more glamorous mayfly hatches are midges. There are days in autumn when midges provide the only opportunity to fish for visibly feeding trout and even more when the fishing hours are extended by these humble little insects. This is because midges do not always require temperatures above freezing for emergence. They may be the first item of attention in the cooler hours of morning, and I have experienced many days of midge fishing until nearly dark when mayfly activity has ended and ice may begin forming in the rod guides.

While different in shape and color, midges mirror the smaller Baetis in size. Therefore, the tactics and techniques are the same for fishing either insect type.

Generally speaking, tippet selection is determined by fly size. Resistance to fishing a very fine tippet seems nearly as pronounced as a reluctance to fish an extremely small imitation. Modern tippet material, and especially Fluorocarbon, gives a comfort not experienced even a decade ago with regard to breaking and knot strength.

The largest trout I have ever landed on the Henry’s Fork took a size 16 fly fished on a 6X tippet. It was a beast of more than twenty six inches in length and probably weighing in excess of seven pounds.

The memory of that great fish provides the confidence to fish even 7X when autumn conditions are at their most demanding. Lower visibility is the obvious benefit of a fine tippet, but I consider its efficiency in reducing drag to be even more important. I am convinced that my success is enhanced by fishing a flexible tippet that will allow the fly to follow the tricky currents of the Henry’s Fork. I fish a 6X tippet routinely throughout the season and will not hesitate to go to 7X when things get especially difficult.

In my experience, anglers traveling great distance to fish the Henry’s Fork have made their decision based on its reputation as a very challenging river. Most keep their expectations in line with that reputation, and their strongest motive is to test themselves against the demands of trout that defy common fly fishing skill.

Ambition for big numbers of trout hooked and landed is not realistic, even for the most accomplished. A more practical objective is the opportunity to experience something distinctly unique in a place where the best of anglers have historically applied their efforts. And this is really all that the legendary Henry’s Fork can ever guarantee.